Irrational number

In mathematics, an irrational number is any real number that cannot be expressed as a ratio a/b, where a and b are integers, with b non-zero, and is therefore not a rational number.

Informally, this means that an irrational number cannot be represented as a simple fraction. Irrational numbers are those real numbers that cannot be represented as terminating or repeating decimals. As a consequence of Cantor's proof that the real numbers are uncountable (and the rationals countable) it follows that almost all real numbers are irrational.[1]

When the ratio of lengths of two line segments is irrational, the line segments are also described as being incommensurable, meaning they share no measure in common.

Perhaps the best-known irrational numbers are: the ratio of a circle's circumference to its diameter Ï , Euler's number e, the golden ratio Φ, and the square root of two â2.[2][3][4]

Contents |

History

It has been suggested that the concept of irrationality was implicitly accepted by Indian mathematicians since the 7th century BC, when Manava (c. 750â690 BC) believed that the square roots of numbers such as 2 and 61 could not be exactly determined,[5] but such claims are not well substantiated and unlikely to be true.[6]

Ancient Greece

The first proof of the existence of irrational numbers is usually attributed to a Pythagorean (possibly Hippasus of Metapontum),[7] who probably discovered them while identifying sides of the pentagram.[8] The then-current Pythagorean method would have claimed that there must be some sufficiently small, indivisible unit that could fit evenly into one of these lengths as well as the other. However, Hippasus, in the 5th century BC, was able to deduce that there was in fact no common unit of measure, and that the assertion of such an existence was in fact a contradiction. He did this by demonstrating that if the hypotenuse of an isosceles right triangle was indeed commensurable with an arm, then that unit of measure must be both odd and even, which is impossible. His reasoning is as follows:

-

- The ratio of the hypotenuse to an arm of an isosceles right triangle is c:b expressed in the smallest units possible.

- By the Pythagorean theorem: c2 = a2+b2 = 2b2. (Since the triangle is isosceles, a = b.)

- Since c2 is even, c must be even.

- Since c:b is in its lowest terms, b must be odd (if it were also even, then both c and b would be divisible by 2, therefore not in lowest terms).

- Since c is even, let c = 2y.

- Then c2 = 4y2 = 2b2

- b2 = 2y2 so b2 must be even, therefore b is even.

- However we have already asserted b must be odd. Since b cannot be both odd and even, here is the contradiction.[9]

Greek mathematicians termed this ratio of incommensurable magnitudes alogos, or inexpressible. Hippasus, however, was not lauded for his efforts: according to one legend, he made his discovery while out at sea, and was subsequently thrown overboard by his fellow Pythagoreans ââ¦for having produced an element in the universe which denied theâ¦doctrine that all phenomena in the universe can be reduced to whole numbers and their ratios.â[10] Another legend states that Hippasus was merely exiled for this revelation. Whatever the consequence to Hippasus himself, his discovery posed a very serious problem to Pythagorean mathematics, since it shattered the assumption that number and geometry were inseparableâa foundation of their theory.

The discovery of incommensurable ratios was indicative of another problem facing the Greeks: the relation of the discrete to the continuous. Brought into light by Zeno of Elea, he questioned the conception that quantities are discrete, and composed of a finite number of units of a given size. Past Greek conceptions dictated that they necessarily must be, for âwhole numbers represent discrete objects, and a commensurable ratio represents a relation between two collections of discrete objects.â[11] However Zeno found that in fact â[quantities] in general are not discrete collections of units; this is why ratios of incommensurable [quantities] appearâ¦.[Q]uantities are, in other words, continuous.â[11] What this means is that, contrary to the popular conception of the time, there cannot be an indivisible, smallest unit of measure for any quantity. That in fact, these divisions of quantity must necessarily be infinite. For example, consider a line segment: this segment can be split in half, that half split in half, the half of the half in half, and so on. This process can continue infinitely, for there is always another half to be split. The more times the segment is halved, the closer the unit of measure will come to zero, but it will never reach exactly zero. This is exactly what Zeno sought to prove. He sought to prove this by formulating four paradoxes, which demonstrated the contradictions inherent in the mathematical thought of the time. While Zenoâs paradoxes accurately demonstrated the deficiencies of current mathematical conceptions, they were not regarded as proof of the alternative. In the minds of the Greeks, disproving the validity of one view did not necessarily prove the validity of another, and therefore further investigation had to occur.

The next step was taken by Eudoxus of Cnidus, who formalized a new theory of proportion that took into account commensurable as well as incommensurable quantities. Central to his idea was the distinction between magnitude and number. A magnitude âwas not a number but stood for entities such as line segments, angles, areas, volumes, and time which could vary, as we would say, continuously. Magnitudes were opposed to numbers, which jumped from one value to another, as from 4 to 5.â[12] Numbers are composed of some smallest, indivisible unit, whereas magnitudes are infinitely reducible. Because no quantitative values were assigned to magnitudes, Eudoxus was then able to account for both commensurable and incommensurable ratios by defining a ratio in terms of its magnitude, and proportion as an equality between two ratios. By taking quantitative values (numbers) out of the equation, he avoided the trap of having to express an irrational number as a number. âEudoxusâ theory enabled the Greek mathematicians to make tremendous progress in geometry by supplying the necessary logical foundation for incommensurable ratios.â[13] Book 10 is dedicated to classification of irrational magnitudes.

As a result of the distinction between number and magnitude, geometry became the only method that could take into account incommensurable ratios. Because previous numerical foundations were still incompatible with the concept of incommensurability, Greek focus shifted away from those numerical conceptions such as algebra and focused almost exclusively on geometry. In fact, in many cases algebraic conceptions were reformulated into geometrical terms. This may account for why we still conceive of x2 or x3 as x squared and x cubed instead of x second power and x third power. Also crucial to Zenoâs work with incommensurable magnitudes was the fundamental focus on deductive reasoning which resulted from the foundational shattering of earlier Greek mathematics. The realization that some basic conception within the existing theory was at odds with reality necessitated a complete and thorough investigation of the axioms and assumptions that comprised that theory. Out of this necessity Eudoxus developed his method of exhaustion, a kind of reductio ad absurdum which âestablished the deductive organization on the basis of explicit axiomsâ¦â as well as ââ¦reinforced the earlier decision to rely on deductive reasoning for proof.â[14] This method of exhaustion is said to be the first step in the creation of calculus.

Theodorus of Cyrene proved the irrationality of the surds of whole numbers up to 17, but stopped there probably because the algebra he used couldn't be applied to the square root of 17.[15] It wasn't until Eudoxus developed a theory of proportion that took into account irrational as well as rational ratios that a strong mathematical foundation of irrational numbers was created.[16]

Middle Ages

In the Middle ages, the development of algebra by Muslim mathematicians allowed irrational numbers to be treated as "algebraic objects".[17] Muslim mathematicians also merged the concepts of "number" and "magnitude" into a more general idea of real numbers, criticized Euclid's idea of ratios, developed the theory of composite ratios, and extended the concept of number to ratios of continuous magnitude.[18] In his commentary on Book 10 of the Elements, the Persian mathematician Al-Mahani (d. 874/884) examined and classified quadratic irrationals and cubic irrationals. He provided definitions for rational and irrational magnitudes, which he treated as irrational numbers. He dealt with them freely but explains them in geometric terms as follows:[19]

"It will be a rational (magnitude) when we, for instance, say 10, 12, 3%, 6%, etc., because its value is pronounced and expressed quantitatively. What is not rational is irrational and it is impossible to pronounce and represent its value quantitatively. For example: the roots of numbers such as 10, 15, 20 which are not squares, the sides of numbers which are not cubes etc."

In contrast to Euclid's concept of magnitudes as lines, Al-Mahani considered integers and fractions as rational magnitudes, and square roots and cube roots as irrational magnitudes. He also introduced an arithmetical approach to the concept of irrationality, as he attributes the following to irrational magnitudes:[19]

"their sums or differences, or results of their addition to a rational magnitude, or results of subtracting a magnitude of this kind from an irrational one, or of a rational magnitude from it."

The Egyptian mathematician AbÅ« KÄmil ShujÄ ibn Aslam (c. 850â930) was the first to accept irrational numbers as solutions to quadratic equations or as coefficients in an equation, often in the form of square roots, cube roots and fourth roots.[20] In the 10th century, the Iraqi mathematician Al-Hashimi provided general proofs (rather than geometric demonstrations) for irrational numbers, as he considered multiplication, division, and other arithmetical functions.[21] AbÅ« Ja'far al-KhÄzin (900â971) provides a definition of rational and irrational magnitudes, stating that if a definite quantity is:[22]

"contained in a certain given magnitude once or many times, then this (given) magnitude corresponds to a rational number. . . . Each time when this (latter) magnitude comprises a half, or a third, or a quarter of the given magnitude (of the unit), or, compared with (the unit), comprises three, five, or three fifths, it is a rational magnitude. And, in general, each magnitude that corresponds to this magnitude (i.e. to the unit), as one number to another, is rational. If, however, a magnitude cannot be represented as a multiple, a part (l/n), or parts (m/n) of a given magnitude, it is irrational, i.e. it cannot be expressed other than by means of roots."

Many of these concepts were eventually accepted by European mathematicians sometime after the Latin translations of the 12th century. Al-HassÄr, a Moroccan mathematician from Fez specializing in Islamic inheritance jurisprudence during the 12th century, first mentions the use of a fractional bar, where numerators and denominators are separated by a horizontal bar. In his discussion he writes, "..., for example, if you are told to write three-fifths and a third of a fifth, write thus,  ." [23] This same fractional notation appears soon after in the work of Leonardo Fibonacci in the 13th century.[24]

." [23] This same fractional notation appears soon after in the work of Leonardo Fibonacci in the 13th century.[24]

During the 14th to 16th centuries, Madhava of Sangamagrama and the Kerala school of astronomy and mathematics discovered the infinite series for several irrational numbers such as Ï and certain irrational values of trigonometric functions. Jyesthadeva provided proofs for these infinite series in the YuktibhÄá¹£Ä.[25]

Modern period

The 17th century saw imaginary numbers become a powerful tool in the hands of Abraham de Moivre, and especially of Leonhard Euler. The completion of the theory of complex numbers in the nineteenth century entailed the differentiation of irrationals into algebraic and transcendental numbers, the proof of the existence of transcendental numbers, and the resurgence of the scientific study of the theory of irrationals, largely ignored since Euclid. The year 1872 saw the publication of the theories of Karl Weierstrass (by his pupil Ernst Kossak), Eduard Heine (Crelle's Journal, 74), Georg Cantor (Annalen, 5), and Richard Dedekind. Méray had taken in 1869 the same point of departure as Heine, but the theory is generally referred to the year 1872. Weierstrass's method has been completely set forth by Salvatore Pincherle in 1880,[26] and Dedekind's has received additional prominence through the author's later work (1888) and the endorsement by Paul Tannery (1894). Weierstrass, Cantor, and Heine base their theories on infinite series, while Dedekind founds his on the idea of a cut (Schnitt) in the system of real numbers, separating all rational numbers into two groups having certain characteristic properties. The subject has received later contributions at the hands of Weierstrass, Leopold Kronecker (Crelle, 101), and Charles Méray.

Continued fractions, closely related to irrational numbers (and due to Cataldi, 1613), received attention at the hands of Euler, and at the opening of the nineteenth century were brought into prominence through the writings of Joseph Louis Lagrange. Dirichlet also added to the general theory, as have numerous contributors to the applications of the subject.

Johann Heinrich Lambert proved (1761) that Ï cannot be rational, and that en is irrational if n is rational (unless n = 0).[27] While Lambert's proof is often said to be incomplete, modern assessments support it as satisfactory, and in fact for its time it is unusually rigorous. Adrien-Marie Legendre (1794), after introducing the BesselâClifford function, provided a proof to show that Ï2 is irrational, whence it follows immediately that Ï is irrational also. The existence of transcendental numbers was first established by Liouville (1844, 1851). Later, Georg Cantor (1873) proved their existence by a different method, that showed that every interval in the reals contains transcendental numbers. Charles Hermite (1873) first proved e transcendental, and Ferdinand von Lindemann (1882), starting from Hermite's conclusions, showed the same for Ï. Lindemann's proof was much simplified by Weierstrass (1885), still further by David Hilbert (1893), and was finally made elementary by Adolf Hurwitz and Paul Gordan.

Example proofs

Square roots

The square root of 2 was the first number to be proved irrational and that article contains a number of proofs. The golden ratio is the next most famous quadratic irrational and there is a simple proof of its irrationality in its article. The square roots of all numbers which are not perfect squares are irrational and a proof may be found in quadratic irrationals.

General roots

The proof above for the square root of two can be generalized using the fundamental theorem of arithmetic which was proved by Gauss in 1798. This asserts that every integer has a unique factorization into primes. Using it we can show that if a rational number is not an integer then no integral power of it can be an integer, as in lowest terms there must be a prime in the denominator which does not divide into the numerator whatever power each is raised to. Therefore if an integer is not an exact kth power of another integer then its kth root is irrational.

Logarithms

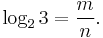

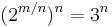

Perhaps the numbers most easily proved to be irrational are certain logarithms. Here is a proof by reductio ad absurdum that log2 3 is irrational. Notice that log2 3 â 1.58 > 0.

Assume log2 3 is rational. For some positive integers m and n, we have

It follows that

However, the number 2 raised to any positive integer power must be even (because it will be divisible by 2) and the number 3 raised to any positive integer power must be odd (since none of its prime factors will be 2). Clearly, an integer can not be both odd and even at the same time: we have a contradiction. The only assumption we made was that log2 3 is rational (and so expressible as a quotient of integers m/n with n â 0). The contradiction means that this assumption must be false, i.e. log2 3 is irrational, and can never be expressed as a quotient of integers m/n with n â 0.

Cases such as log10 2 can be treated similarly.

Transcendental and algebraic irrationals

Almost all irrational numbers are transcendental and all transcendental numbers are irrational: the article on transcendental numbers lists several examples. e r and Ï r are irrational if r â 0 is rational; eÏ is irrational.

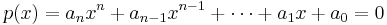

Another way to construct irrational numbers is as irrational algebraic numbers, i.e. as zeros of polynomials with integer coefficients: start with a polynomial equation

where the coefficients ai are integers. Suppose you know that there exists some real number x with p(x) = 0 (for instance if n is odd and an is non-zero, then because of the intermediate value theorem). The only possible rational roots of this polynomial equation are of the form r/s where r is a divisor of a0 and s is a divisor of an; there are only finitely many such candidates which you can all check by hand. If neither of them is a root of p, then x must be irrational. For example, this technique can be used to show that x = (21/2 + 1)1/3 is irrational: we have (x3 â 1)2 = 2 and hence x6 â 2x3 â 1 = 0, and this latter polynomial does not have any rational roots (the only candidates to check are ±1).

Because the algebraic numbers form a field, many irrational numbers can be constructed by combining transcendental and algebraic numbers. For example 3Ï + 2, Ï + â2 and eâ3 are irrational (and even transcendental).

Decimal expansions

The decimal expansion of an irrational number never repeats or terminates, unlike a rational number.

To show this, suppose we divide integers n by m (where m is nonzero). When long division is applied to the division of n by m, only m remainders are possible. If 0 appears as a remainder, the decimal expansion terminates. If 0 never occurs, then the algorithm can run at most m â 1 steps without using any remainder more than once. After that, a remainder must recur, and then the decimal expansion repeats.

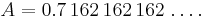

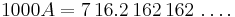

Conversely, suppose we are faced with a recurring decimal, we can prove that it is a fraction of two integers. For example:

Here the length of the repitend is 3. We multiply by 103:

Note that since we multiplied by 10 to the power of the length of the repeating part, we shifted the digits to the left of the decimal point by exactly that many positions. Therefore, the tail end of 1000A matches the tail end of A exactly. Here, both 1000A and A have repeating 162 at the end.

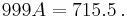

Therefore, when we subtract A from both sides, the tail end of 1000A cancels out of the tail end of A:

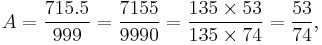

Then

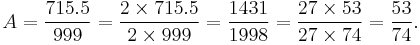

(135 is the greatest common divisor of 7155 and 9990). Alternatively, since 0.5 = 1/2, one can clear fractions by multiplying the numerator and denominator by 2:

(27 is the greatest common divisor of 1431 and 1998).

53/74 is a quotient of integers and therefore a rational number.

Irrational powers

Dov Jarden gave a simple non-constructive proof that there exist two irrational numbers a and b, such that ab is rational.[28]

Indeed, if â2â2 is rational, then take a = b = â2. Otherwise, take a to be the irrational number â2â2 and b = â2. Then ab = (â2â2)â2 = â2â2·â2 = â22 = 2 which is rational.

Although the above argument does not decide between the two cases, the GelfondâSchneider theorem shows that â2â2 is transcendental, hence irrational. This theorem states that if a and b are both algebraic numbers, and a is not equal to 0 or 1, and b is not a rational number, then any value of ab is a transcendental number (there can be more than one value if complex number exponentiation is used).

Open questions

It is not known whether Ï + e or Ï â e is irrational or not. In fact, there is no pair of non-zero integers m and n for which it is known whether mÏ + ne is irrational or not. Moreover, it is not known whether the set {Ï, e} is algebraically independent over Q.

It is not known whether Ïe, Ï/e, 2e, Ïe, Ïâ2, ln Ï, Catalan's constant, or the EulerâMascheroni gamma constant γ are irrational.[29][30][31]

The set of all irrationals

Since the reals form an uncountable set, of which the rationals are a countable subset, the complementary set of irrationals is uncountable.

Under the usual (Euclidean) distance function d(x, y) = |x â y|, the real numbers are a metric space and hence also a topological space. Restricting the Euclidean distance function gives the irrationals the structure of a metric space. Since the subspace of irrationals is not closed, the induced metric is not complete. However, being a G-delta setâi.e., a countable intersection of open subsetsâin a complete metric space, the space of irrationals is topologically complete: that is, there is a metric on the irrationals inducing the same topology as the restriction of the Euclidean metric, but with respect to which the irrationals are complete. One can see this without knowing the aforementioned fact about G-delta sets: the continued fraction expansion of an irrational number defines a homeomorphism from the space of irrationals to the space of all sequences of positive integers, which is easily seen to be completely metrizable.

Furthermore, the set of all irrationals is a disconnected metrizable space. In fact, the irrationals have a basis of clopen sets so the space is zero-dimensional.

See also

- Dedekind cut

- Proof that e is irrational

- Proof that Ï is irrational

- Trigonometric number

- Transcendental number

- nth root

- Square root of 3

- Computable number

References

- ^ Cantor, Georg (1955, 1915). Philip Jourdain. ed. Contributions to the Founding of the Theory of Transfinite Numbers. New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0486600451. http://www.archive.org/details/contributionstot003626mbp.

- ^ The 15 Most Famous Transcendental Numbers. by Clifford A. Pickover. URL retrieved 24 October 2007.

- ^ http://www.mathsisfun.com/irrational-numbers.html; URL retrieved 24 October 2007.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W., "Irrational Number" from MathWorld. URL retrieved 26 October 2007.

- ^ T. K. Puttaswamy, "The Accomplishments of Ancient Indian Mathematicians", pp. 411â2, in Selin, Helaine; D'Ambrosio, Ubiratan (2000). Mathematics Across Cultures: The History of Non-western Mathematics. Springer. ISBN 1402002602.

- ^ Boyer (1991). "China and India". p. 208. "It has been claimed also that the first recognition of incommensurables is to be found in India during the Sulbasutra period, but such claims are not well substantiated. The case for early Hindu awareness of incommensurable magnitudes is rendered most unlikely by the lack of evidence that Indian mathematicians of that period had come to grips with fundamental concepts."

- ^ Kurt Von Fritz (1945). "The Discovery of Incommensurability by Hippasus of Metapontum". The Annals of Mathematics.

- ^ James R. Choike (1980). "The Pentagram and the Discovery of an Irrational Number". The Two-Year College Mathematics Journal..

- ^ Kline, M. (1990). Mathematical Thought from Ancient to Modern Times, Vol. 1. New York: Oxford University Press. (Original work published 1972). p.33.

- ^ Kline 1990, p. 32.

- ^ a b Kline 1990, p.34.

- ^ Kline 1990, p.48.

- ^ Kline 1990, p.49.

- ^ Kline 1990, p.50.

- ^ Robert L. McCabe (1976). "Theodorus' Irrationality Proofs". Mathematics Magazine..

- ^ Charles H. Edwards (1982). The historical development of the calculus. Springer.

- ^ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., "Arabic mathematics: forgotten brilliance?", MacTutor History of Mathematics archive, University of St Andrews, http://www-history.mcs.st-andrews.ac.uk/HistTopics/Arabic_mathematics.html..

- ^ Matvievskaya, Galina (1987). "The Theory of Quadratic Irrationals in Medieval Oriental Mathematics". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 500: 253â277 [254]. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb37206.x.

- ^ a b Matvievskaya, Galina (1987). "The Theory of Quadratic Irrationals in Medieval Oriental Mathematics". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 500: 253â277 [259]. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb37206.x

- ^ Jacques Sesiano, "Islamic mathematics", p. 148, in Selin, Helaine; D'Ambrosio, Ubiratan (2000). Mathematics Across Cultures: The History of Non-western Mathematics. Springer. ISBN 1402002602.

- ^ Matvievskaya, Galina (1987). "The Theory of Quadratic Irrationals in Medieval Oriental Mathematics". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 500: 253â277 [260]. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb37206.x.

- ^ Matvievskaya, Galina (1987). "The Theory of Quadratic Irrationals in Medieval Oriental Mathematics". Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 500: 253â277 [261]. doi:10.1111/j.1749-6632.1987.tb37206.x.

- ^ Cajori, Florian (1928), A History of Mathematical Notations (Vol.1), La Salle, Illinois: The Open Court Publishing Company pg. 269.

- ^ (Cajori 1928, pg.89)

- ^ Katz, V. J. (1995), "Ideas of Calculus in Islam and India", Mathematics Magazine (Mathematical Association of America) 68 (3): 163â74.

- ^ Salvatore Pincherle (1880). "Saggio di una introduzione alla teorica delle funzioni analitiche secondo i principi del prof. Weierstrass". Giornale di Matematiche.

- ^ J. H. Lambert (1761). "Mémoire sur quelques propriétés remarquables des quantités transcendentes circulaires et logarithmiques". Histoire de l'Académie Royale des Sciences et des Belles-Lettres der Berlin: 265â276.

- ^ George, Alexander; Velleman, Daniel J. (2002). Philosophies of mathematics. Blackwell. pp. 3â4. ISBN 0-631-19544-0.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W., "Pi" from MathWorld.

- ^ Weisstein, Eric W., "Irrational Number" from MathWorld.

- ^ Some unsolved problems in number theory

Further reading

- Adrien-Marie Legendre, Ãléments de Géometrie, Note IV, (1802), Paris

- Rolf Wallisser, "On Lambert's proof of the irrationality of Ï", in Algebraic Number Theory and Diophantine Analysis, Franz Halter-Koch and Robert F. Tichy, (2000), Walter de Gruyer

External links

- Zeno's Paradoxes and Incommensurability (n.d.). Retrieved April 1, 2008

|

|||||||||||

)

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

) )

)